But the film’s central storyline is, in the grand tradition of “historical” films, decidedly off-the-record: it focuses on the budding love between Akbar and his first Rajput bride (called, per popular legend, Jodhaa, though her actual name is debated by historians), and alleging that it was her proud and stubborn allegiance to Hindu lifeways that was instrumental in shaping the emperor’s adult personality and policies. This much is a matter of historical record, though the emperor’s motives have predictably been subject to varying interpretations (whereas early Congress leaders tended to project him as a broadminded symbol of an enlightened “secularism,” latter-day Hindu nationalists often portray him as a wolf in sheep’s clothing, co-opting guileless Hindus with an only superficially kinder, gentler Islam). Notably, he does so through a strategic marriage to the daughter of a key ally, the Rajput king of Amer, and through his decision, roughly a year later, to abolish the pilgrimage tax on non-Muslims, a signal of his growing tolerance for the religion of the majority of his subjects and of his willingness to defy more orthodox Islamic elements within his court.

With the exception of a brief prologue, most of the action unfolds between 15, the period that saw the twenty-year-old Akbar (who ascended the throne at age fourteen on his father Humayun’s death, but was initially overshadowed by a regent) asserting his own personality and policies. The most dramatic thing that happens-Akbar’s temporary exile of his bride on the suspicion that she is betraying him, which occurs just before Interval-is cleared up within fifteen minutes of the film’s resumption, and we again settle back into what is essentially a pleasantly protracted coming-of-age story, albeit its subject is a singularly remarkable pre-modern ruler. There are acres of glittering fabrics, Persianate gardens aflutter with pigeons and doves, and even a mouthwatering multicourse meal that should send you running to the nearest tandoori-joint buffet.ĭon’t expect much suspense, though. This is also, in a way, a “consumerist” film that continues the pattern of display of conspicuous goodies established by middle-class blockbusters like HUM AAPKE HAIN KOUN and DIL CHAHTA HAI, though here with an “ethno-historic” sensibility: Jodhaa’s lacquered boudoir and Akbar’s jewel-encrusted outfits set a new standard in desi chic. Other influences may include Chinese historical and martial-arts films, as reflected in a well-choreographed his-and-her sword duel that seems indebted to Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon.

Jodha akbar songs movie#

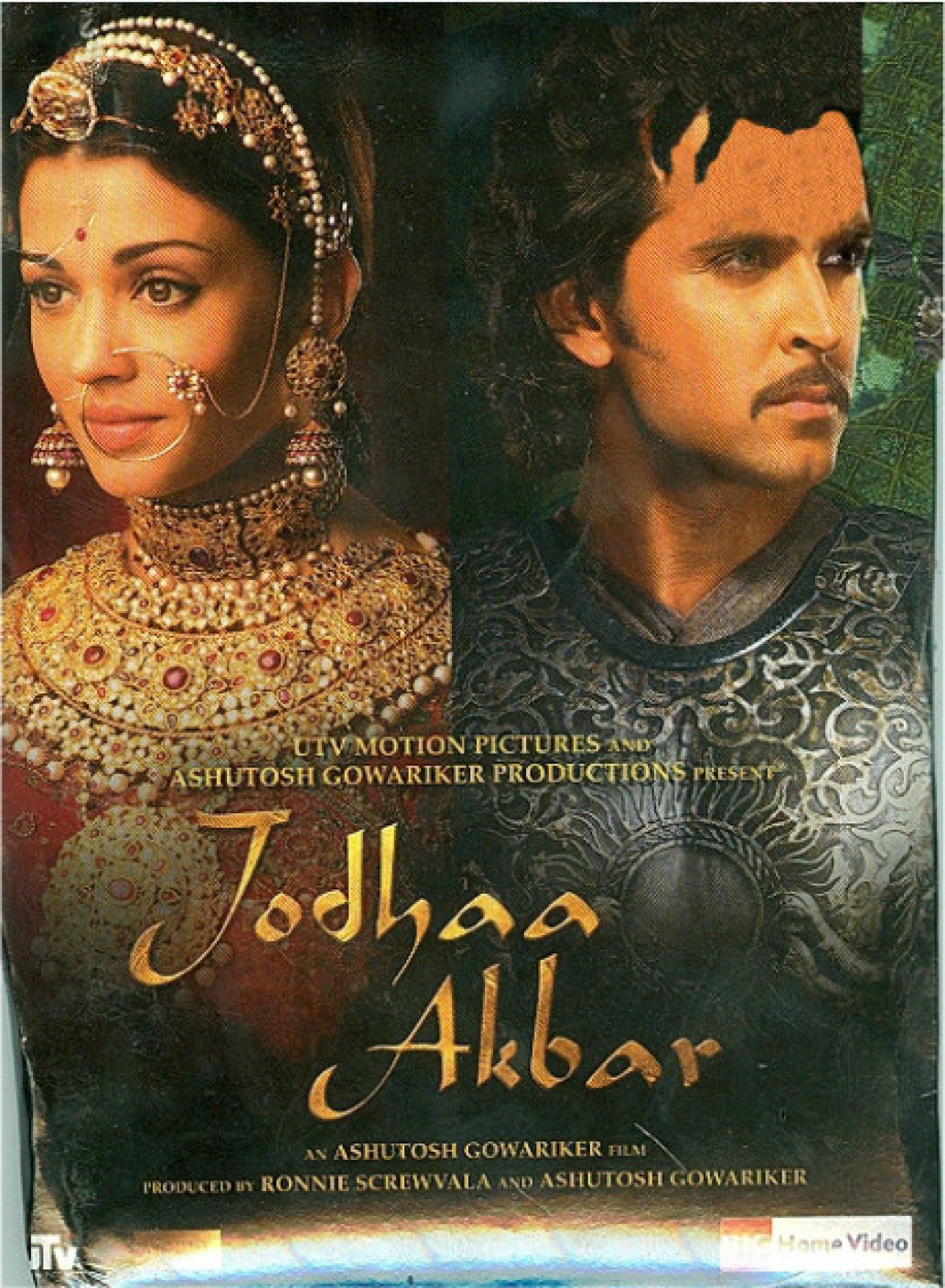

Indeed, everything about the movie is gorgeously beautiful, beginning with the principal players, and (though the storyline takes arguable liberties with known history) production values are sky-high and obvious visual anachronisms relatively few-the most striking perhaps being Jodhaa’s Krishna statuette, which looks like a 19th-century German porcelain rather than the big-eyed, black stone murtis typical of the Mughal period. It’s a bit like taking a vacation in 16th century North India, without the risk of contracting plague or being decapitated by a warlord. The best approach to it (now that it’s out on DVD, with its long halves neatly divided between two disks) is to find a comfortable couch on an unhurried evening (or two) and just let it wash over you. Rahman music, unexpectedly strong performances, and an obvious but unobjectionable didactic message (the promotion of inter-religious tolerance, especially between Hindus and Muslims). More truly “historical” in subject matter but far looser in plot, JODHAA AKBAR is an essentially atmospheric experience of breathtaking cinematography and mise-en-scène, lovely A. In the grand tradition of Indian (and Bombay cinematic) storytellers, Gowariker is unwilling to send anyone home in under three-plus hours his remarkable debut film, LAGAAN, acclaimed as a revival of the rarely-made genre of the “historical,” was a tautly-paced underdog sports saga set in the colonial period that kept viewers on the edge of their seats for nearly four.

Rahman cinematography: Kiiran Deohans production design: Nitin Chandrakant Desai costume design: Neeta LullaĪshutosh Gowariker’s sumptuous tribute to the Mughal Empire at the height of its culturally-syncretic glory unfolds with the leisurely gait of an imperial elephant. Story: Haidar Ali screenplay: Haidar Ali and Ashutosh Gowariker dialogues: K.

Produced by Ronnie Screwvala and Ashutosh Gowariker

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)